Originally published on Facebook November 19, 2021.

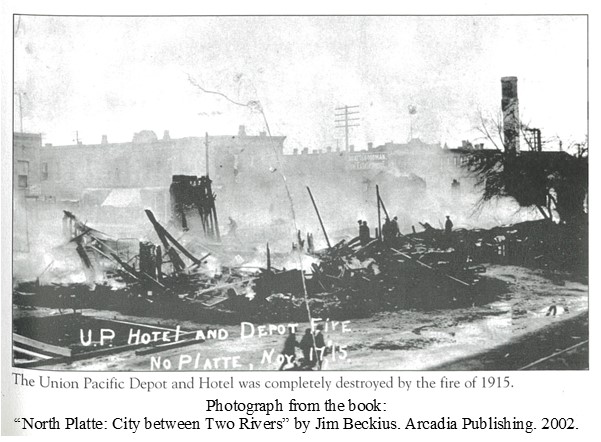

Today’s Facebook Friday North Platte history looks at the Union Pacific Depot fire of 1915, which occurred 106 years ago.

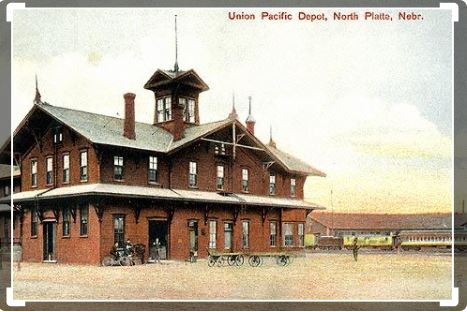

The North Platte Semi Weekly Tribune announced that the fire occurred Wednesday, November 17, 1915, and the 46 year old depot, located at Front and Dewey Streets, that served as both a hotel and railroad depot had burned to the ground. It was considered one of the biggest fires in North Platte in over twenty years. You can see in the postcards that the original depot was an all-wood structure.

The paper reported that during the depot’s lifetime, it had caught on fire several times, due to sparks from locomotives. But every time a fire started, alert workers were there to extinguish the flames. The fire that finally took down the Depot was believed to of started from cinder from the stack of a locomotive that fell onto the building around 3:30 pm that afternoon. The live cinder that started the fire was lodged in a crevice between the platform and the siding near the center of the north side of the west wing of the building. The cinder was fanned by a strong wind that ignited the siding. It was then discovered by manager John McDonald after burning a one-foot hole. After using water to extinguish the fire the men went on their way, not realizing that embers had already crept up between the walls and into the attic of the depot. The fire was still smoldering.

An hour later smoke was seen rolling out from under the eaves, and the fire department was called. Once the firemen got there and started putting water on the building the fire broke through the roof and the strong winds caused it to collapse. By eight o’clock, nothing was left standing, except two chimneys. The depot and hotel were completely demolished.

During the fire, people ran into the burning building, trying to save whatever they could. Some of the items saved were: property from the ticket office and baggage room; valuables in the hotel office; and silverware, linen and furnishings from the dining room. When the fire started several railroad workers were asleep in their hotel rooms and all successfully escaped with their belongings. Buildings in the vicinity were carefully watched as the wind was from the northwest blowing cinders/embers across the street towards those buildings.

The Depot that burned down in 1915, was built in 1869 and completed shortly before Christmas that year. That depot was actually the SECOND depot, replacing the first depot which burned down on July 4, 1869.

On April 16, 1912 a new proposal was brought to the attention of North Platte Citizens. The President of the railroad proposed $336,000 for a new round house, coal shuts and other terminal improvements. In that proposal, $85,000 would go for a new depot. He said the citizens of North Platte had to decide what they wanted most. The new Depot or all of the other railroad improvements as he didn’t believe the directors of the railroad would approve the funding for all of his proposal.

On January 29, 1914, the North Platte Telegraph wrote that Senator Hoagland from North Platte had filed a petition before the state railroad commission for the construction of a new depot at North Platte. He demanded an answer by February 9, 1914. Hoaglund stated in his petition that the amount of business that is done in North Platte, by the railroad, required a bigger depot. The old depot was built when North Platte was just a frontier town; with trade and traffic just a fraction as it had grown to be by 1914. He stated that the railroad had built many new shops, switched facilities to handle the increasing number of trains coming through, but has neglected to spend their money on the depot to handle the public usage. North Platte was considered a principal station between Council Bluffs, Iowa and Ogden, Utah. Not only had the amount of baggage that comes through outgrown the size of the baggage room, the waiting room in the depot was like sitting in a “pig-pen.” The toilet facilities were a disgrace. There were no ladies facilities and the waiting room was too small for the amount of passengers arriving each day.

On February 5, 1914, the City Council announced that the petition was to be withdrawn. They stated that the city had recommended that the railroad build a new roundhouse and not a new depot. They trusted that the railroad would in turn supply the city with a new depot when the railroad saw fit.

A year later, the problem was taken care of with the burning of the depot. A new brick structure was constructed as the North Platte Depot and dedicated in March of 1918. It is this is the depot that many of our readers remember . The location of this depot was at 300 East Front Street. The cost to build the new structure in 1917 was $160,000.

If you want to learn more about the North Platte Canteen, please consider reading Bob Greene’s book “Once Upon a town” and James Reisdorff’s book “The North Platte Canteen. In addition, the Lincoln County Museum also has a wonderful Canteen exhibit where you can learn more about the Union Pacific Depot and the History of the North Platte Canteen.

Copies of either book may be borrowed from the North Platte Public Library or purchased from A to Z books or the Lincoln County Historical Museum.

Thank you for reading and we will see you next week for more North Platte History!