Originally published to facebook.com/NorthPlattePL on June 24, 2022.

Welcome back to another Facebook Friday History!

Today’s history looks at the early days of the Union Pacific Railroader and a strong Irish-Catholic who led an amazing career working for the Railroad, George Ambrose Austin.

George A. Austin was born April 1851 in Kilballyowen, Clare, Ireland to Patrick and Catherine (Connors) Austin. George was eleven years old when they immigrated to the United States, settling in 1862 at Pittsfield, Illinois. His father was a day laborer, and both his parents died in Pittsfield. George had one sibling, a sister, Jane Austin.

In 1874, George married Elizabeth Louise McGinn (1854-1930) in Pittsfield, Illinois. They had four children:

1. George Thomas Austin (1874-1974, Born in North Platte, NE). He owned an automotive garage in Pasco, Washington;

2. Mary Ellen “Nellie” Austin (1876-1965, born in North Platte, NE), who married E.F. Seeberger, President of First National Bank in North Platte;

3. Margaret “Theresa” Austin (1882-1964, born in North Platte, NE), who married Joseph B. Hayes and lived in Omaha; and

4. Charles Patrick Austin (1885-1961), a clothier in Bakersfield, California.

He began his railroad career when he was 21 years old as a section foreman in Roscoe, Nebraska. He worked his way up and within a year became a fireman. George moved to North Platte in May of 1874, where he continued to work as a fireman for the Union Pacific. In 1881, he was promoted to engineer. The next year, he was initiated into Division 88, Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE). George had a forty-six-year career with the Union Pacific Railroad.

George lived in a house at 417 East 5th Street and the family lived there until his death on January 11, 1928.

On August 21, 1895, George had a night he would never forget. On that night, he was on Train No. 8 and it was a half an hour late leaving North Platte. As the train approached Brady Island, there was a signal to stop and take on passengers. The stop was short, because they were trying to make up time.

George and his fireman saw two men leap onto the baggage car next to the engine, and almost before they realized it, George heard the fireman say, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot!” Looking back, Austin saw the two men coming over the coal box, one man with two pistols and one man with a Winchester rifle.

George tried to stop the train, but the bandits told him to keep going, and they would tell him when to stop. He followed their instructions, all the while trying to figure out how to get the bandits off the train.

The bandits told him to run through a curve. They would tell him when and where to stop the train. George could not talk or communicate with his other UP trainmen to put any plan together to escape or take down the bandits.

Once the bandits ordered the train to be stopped, the bandits ordered George to rap on the door of the express car; and when the messenger opened it they entered and compelled the man to open the local safe. After rifling through it, the bandits stole the $150.00 in it and ordered another safe to be opened. But the second safe could only be opened by a train station agent and no one was able to open it. The robbers then produced a sack of dynamite to blow the big safe open, and set the explosives. Then, every person left that train car to allow the dynamite time to explode.

Meanwhile, Austin convinced them to move further away from the safe, for everybody’s safety. The desperado remarked, “The damned thing isn’t going off,” and he started back to investigate, but then changed his mind and came back to Mr. Austin. And in the meantime, George Austin had put together a plan to get help. He asked for a volunteer to sneak back to the engine, uncouple it and escape to go get help when the explosives went off. Fireman Tom Duke quietly volunteered and the plan was put into motion. Dukes slipped away from the trainmen and got to the engine to start uncoupling it and preparing it to make a getaway.

The dynamite finally exploded and the robbers hurried back to the express car, only to find the outside door blown off of the safe. During the setting of the explosives, up until the moment of the explosion, a fireman uncoupled the engine; and escaped, taking the train engine to Gothenburg, where he spread the alarm.

The bandits were frightened and mounted their horses and disappeared into the night. If they had been able to get into the big safe, the bandits would have stolen approximately $13,000. This would be worth about $450,000 in today’s dollars.

As the bandits escaped the scene of the crime, one of the horses went lame after going through a barbed wire fence, so both men escaped on one horse.

After a few days of being “in hiding,” the men walked into Mason City, Nebraska, where they ordered breakfast. The Mason City railway agent happened to see them there and concluded they fit the description he had read about in the alarms and bulletins. The agent hurried to go find the marshal. When the bandits finished their breakfast, they started on foot, walking down the train tracks.

After they walked out of town a while, the bandits stopped to cool off in a stream, not knowing that lawmen and deputies were on their trail. By the time they were done in the water, the marshal appeared and ordered them out of the water. The men were arrested and charged. The thieves turned out to be Hans and Knute Knudsen from Dakota County. They plead guilty and were sentenced to ten years in the penitentiary within ten days of committing this crime.

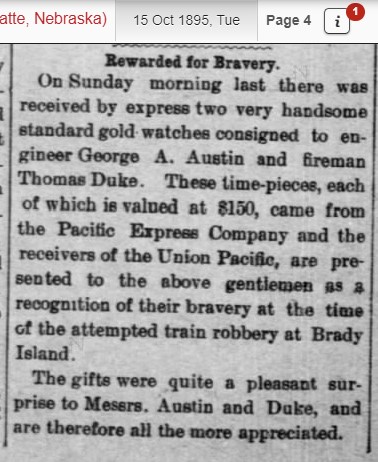

In October of 1895, George Austin and Tom Duke received a gold watch for their bravery at the Brady Island train robbery. The watch cases were inscribed with “Presented to George Austin and Tom Duke by the Receivers of the Union Pacific and Pacific Express companies, for meritorious conduct at the train robbery near Brady Island on the night of August 21, 1895.”

George Austin died on January 11, 1928 after suffering with a stomach ailment for two months. He was 76 years old. George was a member of the Knights of Columbus and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers.

After his death, his wife, Eliza moved in with her daughter Nellie. She passed away in 1930, at age 76 after suffering a stroke.

Thank you for reading! And, be sure to visit the Lincoln County Historical Museum, where you can see the Brady Island Train Depot and more Lincoln County History! See you next week!

#NPHistoryArchives