Originally published to facebook.com/NorthPlattePL on April 1, 2022.

Last Friday, we looked at the history behind the establishment of the Lincoln Highway/Highway 30. This week, we look at how Highway 30 coming through North Platte affected our community and county. Next week we will look at the development of “auto courts” in North Platte along the Lincoln Highway and one unique Nebraskan automotive family, popular in the 1930’s-1940’s.

Some of the highlights of today’s post include;

- The early concerns that the route of the Lincoln Highway would be along the southern part of the state (Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, McCook);

- The improvements and “straightening” the route over the years;

- The Army Convoy of 1919;

- The marking of the Lincoln Highway by the Boy Scouts of America; and,

- The last concrete completion of the Lincoln Highway road took place just west of North Platte

If you remember, the year was 1912 and most roads were dirt or sand and didn’t necessary connect. The purpose of the original Lincoln Highway was to connect the roads, create one road that would connect the East and West coasts, and a project that would improve this road. Once this movement had momentum, 1913 was a very busy year in the planning for the Lincoln Highway to go through North Platte:

Sept 16, 1913 – North Platte found out that the Lincoln Highway would come through the state of Nebraska.

Sept 18, 1913 – The proposed route of the Lincoln Highway through Nebraska would be: Omaha, Fremont, Columbus, Central City, Grand Island, Kearney, Lexington, Gothenburg, North Platte, Ogallala, Big Springs, Chappell, Sidney and Kimball.

Sept 26, 1913 – A Lincoln Highway Convention (called the Good Roads Committee), would be held in Detroit, Michigan in about 4 days, and delegates were invited to attend. Thomas C. Patterson was elected as local North Platte/Lincoln County delegate and left immediately for Detroit.

Sept 26, 1913 – The Platte Valley Transcontinental Highway Association met in Central City, Nebraska on October 8, 1913. The purpose of said meeting was to provide ways and means of raising about $2,000 per mile for the Lincoln Highway across the state.

Sept 30, 1913 – Thomas Patterson reported from Detroit that the route through Nebraska was not definitely set, and that there was a petition movement proposing that Highway 30 go through the southern part of Nebraska: Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, and McCook, then on to Denver. Remember that Denver was excluded from the original Lincoln Highway and as a political good-will gesture, a loop was originally put in and then taken out later.

Oct 3, 1913 – At the Good Roads meeting in Detroit, it was decided that the location of the Lincoln Highway through Nebraska would follow the Transcontinental Route (through North Platte). The decision was made because there were more existing roads to connect, the Union Pacific already had connection points due to the railroad, and it was a more direct route. With the routes near the Union Pacific, it was hoped that the UP would help fund the roads, and they did. The delegates also got to see the concrete roads around Detroit and it was hoped that the Lincoln Highway roads would be improved to be concrete roads. Another topic discussed at this meeting was the cost needed to get the Lincoln Highway started. That target funding goal was ten million dollars. The plan was to have businesses, individuals, and communities started fund-raising campaigns for the construction.

Oct 7, 1913 – Articles ensued about the cost of the Lincoln Highway. The average cost through Nebraska was going to be about $8,000 per mile. And the road through Lincoln County would be nearly sixty miles in Length and the cost would be over $450,000.

Oct 17, 1913 – The Lincoln Highway Commission requested that in locating the road through Nebraska, all turns, if at all possible, must be eliminated in order to shorten the route.

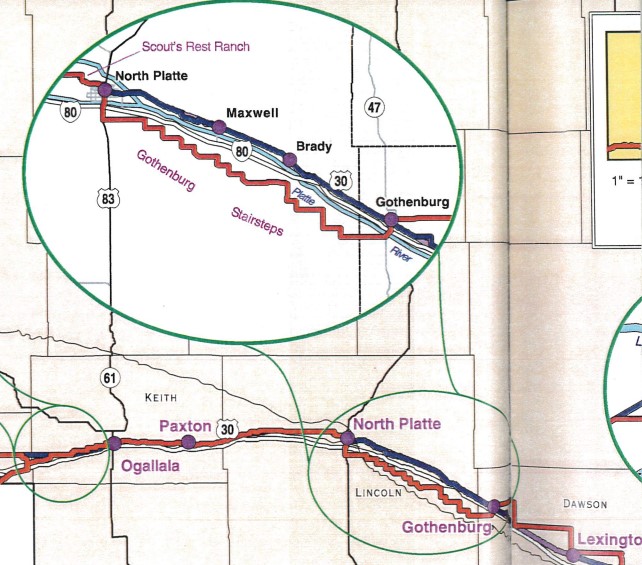

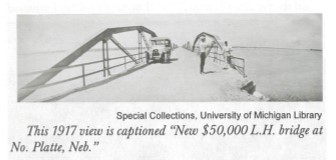

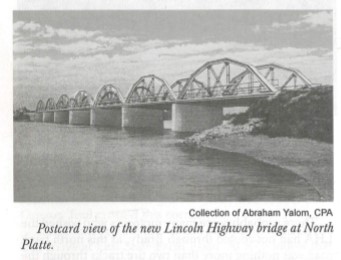

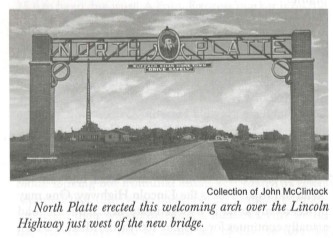

Oct 26, 1913 – The original route from Gothenburg to North Platte was planned as a “stair step” road, changing directions every few miles. It was suggested that if a permanent bridge were constructed east of North Platte, it would save 18 miles and be a more direct route. The cost for the bridge would be $50,000. Twenty-five thousand dollars would come from the state; $12,500 would be paid through a levy by the Union Pacific Railroad; and the remaining $12,500 would come from the people of six eastern Lincoln County precincts and the residents of North Platte. The bridge construction meant that the Lincoln Highway route would be straightened and shortened. Thereby making Highway 30 coming into the city on East 4th Street, not Jeffers Street.

Researchers Note: In case you are wondering, why would the Highway between Gothenburg and North Platte have the “stair step pattern?” Well, the railroad owned much of the land that the Lincoln Highway was following and because part of the original intent was to “see America,” the Highway went through many towns and villages. So the road winded through the towns, utilizing the existing roads and railroad crossings, and created the stair-step. If you look at the map, you can easily see why the straightening of the route was more desirable than the stair step.

Nov 7, 1913 – The bond issue for the new $50,000 bridge passed at the County Commissioners meeting. Researchers note: although the bridge bond passed, it was a few years before the bridge was completed and the Lincoln Highway route changes (that happened around 1915/1916).

Dec 4, 1913 – Lincoln Highway Marker colors and designs were selected. The official Lincoln Highway marker stands 21 inches high, and consists of a strip of red three inches high at the top, a white band 21 inches wide and a strip of blue three inches high below the white. On the white background in blue there is a large letter “L” and the words “Lincoln Highway” in smaller type. This marker is to be painted on telegraph poles, barns, fences whatever is available along the highway and which can be readily seen by the tourist.

By 1914, there still wasn’t much of a highway to be concerned about. No improvements had been made to the Lincoln Highway; there was a growing disinterest of people; and the ten-million-dollar fund was stalled at the half-way point. The Highway through Lincoln County is still mainly dirt and sand.

Over the next few years, the road was straightened and the new route was called the 2nd Generation Lincoln Highway.

One of the most successful promotional activities of the Association were called “seedling miles.” With cement donated by the Portland Cement Company and funds raised by local sponsors, one-mile concrete sections were constructed in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Nebraska. On November 3, 1915, Grand Island became the first Nebraska city to complete a seedling mile. Kearney’s was finished two weeks later. Lincoln County did not complete a seedling mile, which may have been a blessing in disguise, as ALL the seedling miles in Nebraska needed repairs after one year.

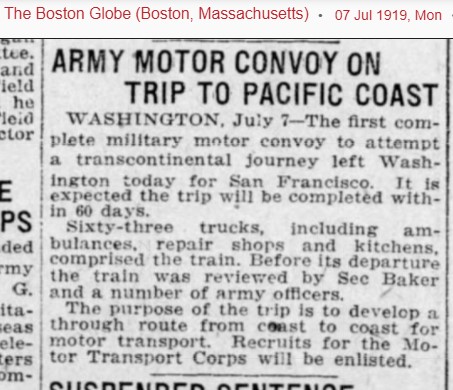

In 1919, the government decided to see if a military convoy could traverse the United States from coast to coast, and planned to use the Lincoln Highway for the majority of the trip. They left on July 7, 1919 and the convoy consisted of 42 trucks, including ambulances, repair shops and kitchens. This was the first motor convoy to attempt a transcontinental journey, starting in Washington and ending in San Francisco. The goal was to complete the journey in 60 days. The convoy was reviewed by Secretary of State Baker and a number of Army officers. The purpose of this trip is to develop a through route from coast to coast for motor transport. See attached newspaper article from the Boston Globe: “Army Motor Convoy on trip to Pacific Coast.

The convoy came through Nebraska during the last days of July 1919. A crowd gathered in Omaha and applauded to welcome the men, among them, General Dwight D. Eisenhower who had recently returned from the Great War. This caravan did not set out to stir up patriotism, though. Rather, the U.S. Army wanted to see if the new transcontinental highway could withstand the weight of military vehicles.

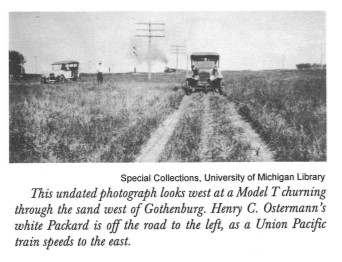

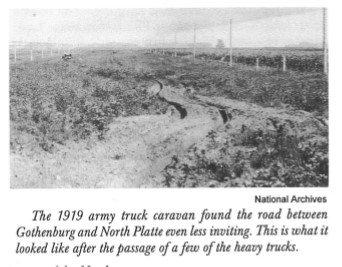

The men in charge of the Army convoy described the trip as rough, and the caravan broke almost every bridge it encountered. An article in The Gothenburg Times, August 6, 1919 had the headline “Army Motor Convoy has first setback in Dawson County Mud: Troop Train Arrived Saturday afternoon after Rough Voyage from Lexington in Mud and Rain. Trip to North Platte Sunday Worse and More of it. Across the United States, the Lincoln Highway road’s weaknesses were made apparent. During his presidency three decades later, Eisenhower instituted the bill that approved the Interstate Highway System. This time in the transcontinental convoy, along with experience with the German Autobahn during World War II, influenced him to establish the interstate highway system (I-80) we know today.

During the 1920’s many of the Lincoln Highway roads continued to be improved by replacing dirt/sand sections with concrete, and the route was “straightened.” As you can see on the attached map, some areas of the state have a third generation straightening. Former Nebraska Department of Roads engineer Walt Heier claimed that the most significant road improvements occurred after 1932.

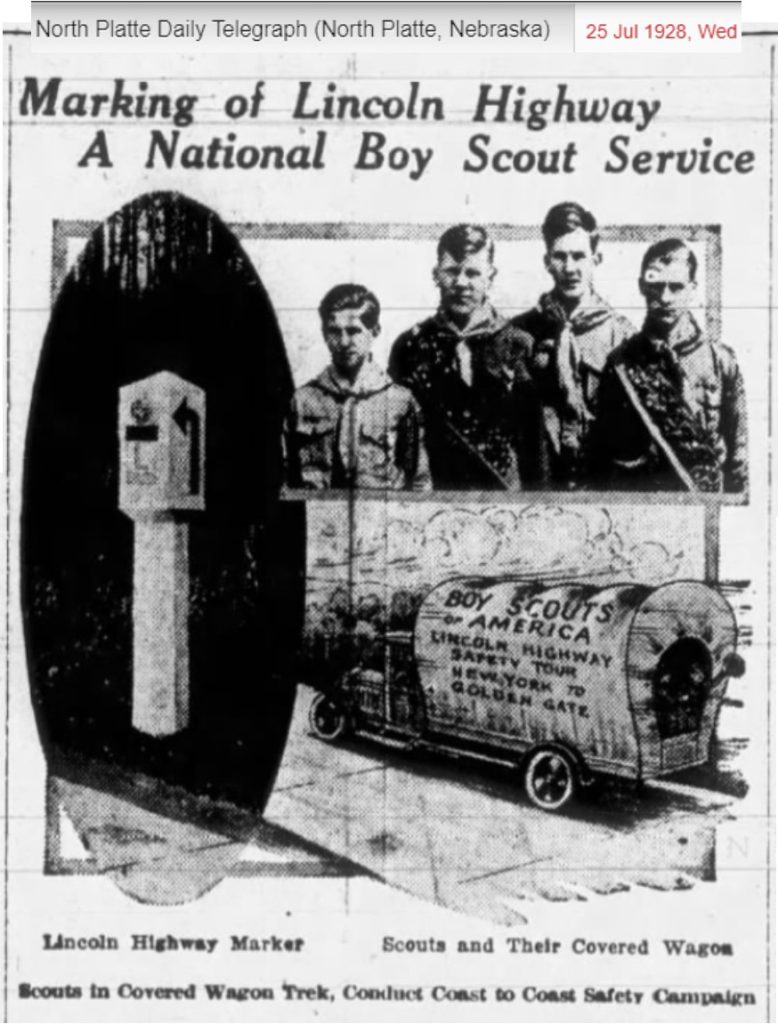

In 1928, the Boy Scouts of America decided to assist in the placing of Lincoln Highway permanent markers in every state. The work was done under the direct supervision of the national committee on safety of which Col Theodore Roosevelt was chairman. Thirty-five Lincoln Highway markers were put up in one day in the fourth week in August. After the marker was installed, the care and maintenance of the marker was assigned to an individual boy scout. On July 25, 1928, a caravan of seventeen Boy Scouts came through North Platte. These boys were selected for general all-around achievement and character from the United States to represent the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America. The object of their tour was to promote the Lincoln Highway Safety program and proper marking/designation of the highway.

And the story of the Lincoln Highway comes full circle with a twist of irony. North Platte/Lincoln County was one of the first in the United States to ratify the Lincoln Highway Proclamation in 1913, but ironically, it was the last place that the Lincoln Highway was paved. In early November 1935, over 3,000 people gathered on Route 30, a few miles west of North Platte. In a nod to the transcontinental railroad’s “Golden Spike,” a golden ribbon was cut. The celebration included a caravan of automobiles, covered wagons pulled by oxen, horse-drawn buggies, and a stagecoach. President Franklin Roosevelt sent a telegram, “Completion of the last link of pavement on U.S. Route 30 is an event of such importance that I am happy to send my congratulations. The perilous trail of the pioneers is at last transformed… into a coast-to-coast highway.”

The highway that had begun as a red line on paper was finished. Today, adventurous travelers can still find Highway 30, the old road, markers, and buildings; from both the original, second and third generation Lincoln Highway.

And if you want to read more about the Lincoln Highway, stop by the Library and check out some wonderful books!

Join us next week as we look at the invention of auto-courts in North Platte for visiting travelers on the Lincoln Highway!

#NPHistoryArchives