I Love the Library because….

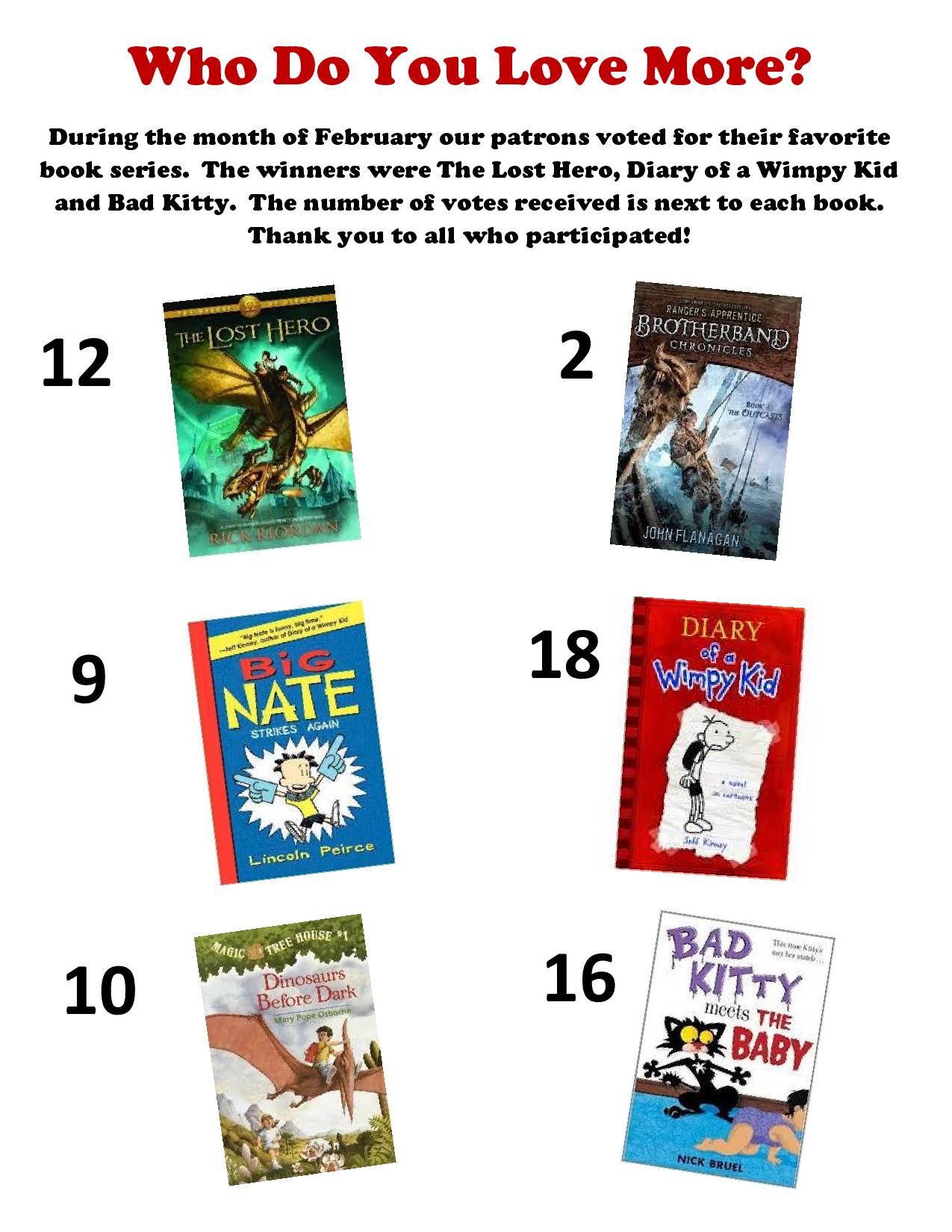

The results are in…

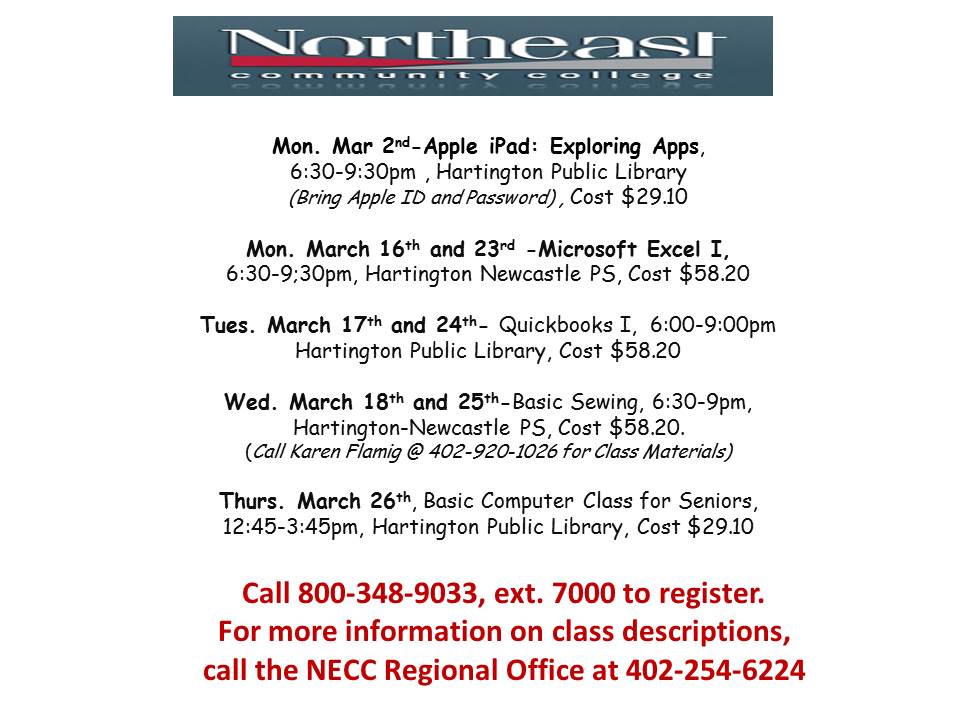

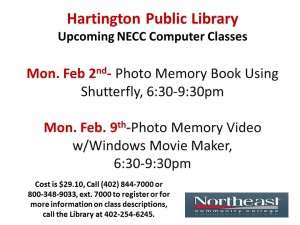

Upcoming NECC Classes In Hartington

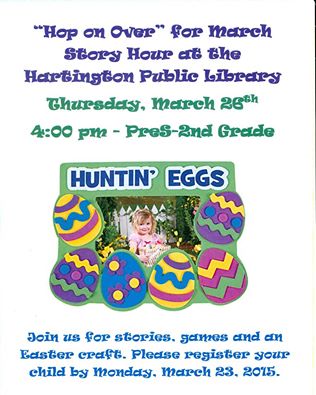

Join us for our Monthly StoryHour next Thursday the 26th!

Read Across America with us!

Don’t forget to call the library to register for the upcoming after school Story Hour!

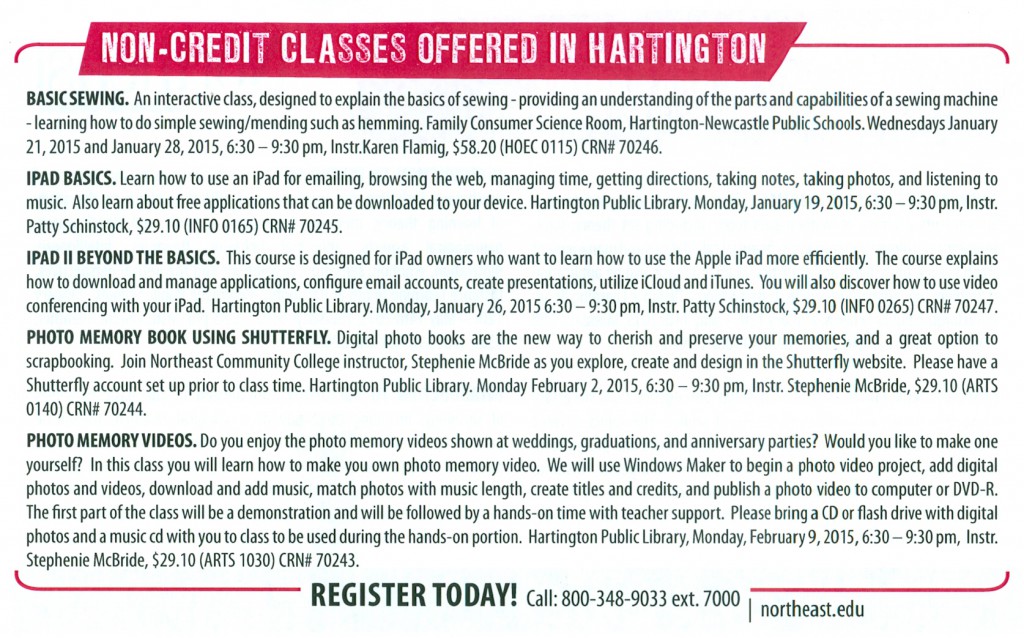

Classes available at the library

20th Award for “1000 Books Before Kindergarten”

Congratulations goes to Maleah Heimes, daughter of Lee and Joan Heimes, Wynot who received her “1000 Books Before Kindergarten” award at the Hartington Public Library. Maleah received a certificate, medal, and a book for her reading accomplishment! She just turned four this fall and is a regular visitor to the fall. Maleah is the 20th child who has completed this program, which means 20,000 books have read read/listened too so far!

This program was developed to instill the love of reading get children ready for school, and to encourage more parent/child library visits. Books are logged along the way. One of the best ways to encourage pre-reading skills is to spend time sharing books each and every day! Reading provides a solid foundation, a key to school and learning success. When you as a parent read to your child, you help him or her develop the skills they will need to learn to read by themselves.

If you are interested in learning more about this reading journey for your child, please stop by or call the library at 402-254-6245.